Day 30 – February 9 – Panamint Springs (Death Valley National Park)

We woke up at 7:30 and had a good breakfast in the little restaurant at Panamint Springs. Walking across the parking lot I saw these two birds. The first one, we learned later, is a Greater Roadrunner, a year-round resident of Death Valley, and the other is a Mountain Chickadee.

After breakfast we began our three-day odessy in Death Valley. There are only three places to stay in Death Valley – Panamint Springs, Stovepipe Wells and Furnace Creek. Furnace Creek is the largest by far. There are no towns in the Park but each accomodation area also has a campground, RV parking, a general store, a restaurant and a gas station. Accomodation is expensive but the meals were only a ‘little’ pricier than normal; unless you go to the Steak House at Furnace Creek Ranch or the Furnace Creek Inn Restaurant; where you will pay BIG BUCKS for your dinner.

After breakfast we began our three-day odessy in Death Valley. There are only three places to stay in Death Valley – Panamint Springs, Stovepipe Wells and Furnace Creek. Furnace Creek is the largest by far. There are no towns in the Park but each accomodation area also has a campground, RV parking, a general store, a restaurant and a gas station. Accomodation is expensive but the meals were only a ‘little’ pricier than normal; unless you go to the Steak House at Furnace Creek Ranch or the Furnace Creek Inn Restaurant; where you will pay BIG BUCKS for your dinner.

We split our explorations geographically and stayed at each of the places. This gave us the opportunity to see many of the Valley’s recommended sites without a lot of back and forth driving. Many people come into Death Valley from the Arizona side and only see the things south and north of Furnace Creek.

Panamint Springs is 30 miles from the western boundry of Death Valley National Park (coming in from Lone Pine, CA), sitting on the western slope of the very long, very flat Panamint Valley. The Panamint Range separates this section of the park from the Stovepipe Wells and Furnace Creek areas which are in Death Valley itself.

Panamint Springs is 30 miles from the western boundry of Death Valley National Park (coming in from Lone Pine, CA), sitting on the western slope of the very long, very flat Panamint Valley. The Panamint Range separates this section of the park from the Stovepipe Wells and Furnace Creek areas which are in Death Valley itself.

We drove about 20 miles west, up through Rainbow Canyon to the Father Crowley Vista Point where you can enjoy a panoramic view of the Panamint Valley and Panamint Range.

If you look closely at this photo you can see the old car wreck rusted on the bank. That would not have been a good ride.

If you look closely at this photo you can see the old car wreck rusted on the bank. That would not have been a good ride.

This plane is about to refuel in mid-air.

This plane is about to refuel in mid-air.

After we had enjoyed the view from Father Crowley’s Point we backtracked down the road to find the turn-off to Darwin Falls which provides the water for Panamint Springs.

Panamint Springs was originally built in the 30’s to provide accomodation and a way-station to serve the miners up in the mountains at Darwin. Without the Darwin Falls there would be no ‘settlement’ here. It is a year-round waterfall found after a 1 mile hike into the canyon at the end of a 7 mile dirt road.

There were some tricky places to navigate along the trail.

There were some tricky places to navigate along the trail.

The pipeline for the water is above the ground 99% of the way to Panamint Springs. Most of it is iron but there were sections that had been replaced with plastic. Several joints had leaks and there would be nice green grass and bushes on the ground underneath the area.

The pipeline for the water is above the ground 99% of the way to Panamint Springs. Most of it is iron but there were sections that had been replaced with plastic. Several joints had leaks and there would be nice green grass and bushes on the ground underneath the area.

When we had spoken to the Park Ranger at Lone Pine he suggested we drive in to the Panamint Dunes which we could see in the distance from Father Crowley’s Vista.

When we had spoken to the Park Ranger at Lone Pine he suggested we drive in to the Panamint Dunes which we could see in the distance from Father Crowley’s Vista.

We initially drove past the turn-off because there was no directional marker and the road was barely visible amidst all the rocky gravel. It took us 1 1/2 hours to drive the 20 miles to the end of the road only to discover the dunes were probably a 2+ mile hike away. We took a few photos and drove 1 1/2 hours of rocky, bumpy ‘road’ back again. It was disappointing to not get close to the dunes but we have seen sand dunes before so we were okay; and it was VERY cool to be out in the middle of such a large desert expanse and experience the absolute quiet. I loved the absence of sound.

These two cars were alongside the road about halfway down and they were absolutely riddled with bullet holes, some of which were a large enough caliber to put a fist-sized whole right through the vehicle.

These two cars were alongside the road about halfway down and they were absolutely riddled with bullet holes, some of which were a large enough caliber to put a fist-sized whole right through the vehicle.

This sand is so dry and hard and windblown you leave no footprints on it.

This sand is so dry and hard and windblown you leave no footprints on it.

In order to go from Panamint Springs to Stovepipe Wells you need to cross the Panamint Range through Towne Pass (Elevation 4956′ at the summit). This route was a originally a private toll road built by the owner of a ‘hotel’ camping ground at Stovepipe Wells. He wanted to encourage tourists to come to Death Valley but road access was non-exsistent. The National Park had not yet been created and he got permission from the State to built a 30.35 mile toll road which the Park Service eventually purchased from him when they made Death Valley a National Monument.

A sign at the bottom of the pass says to turn off your air conditioner for the next 10 miles due to the risk of overheating the engine on the rapid climb in the hot temperatures.

Due to the heavy rains in October the wild flowers are blooming in Death Valley. This only happens every 10-15 years. We spoke to people that have worked in the park for years and have never seen the flowers bloom. We saw many of them along the roadside once we started through Towne Pass.

Due to the heavy rains in October the wild flowers are blooming in Death Valley. This only happens every 10-15 years. We spoke to people that have worked in the park for years and have never seen the flowers bloom. We saw many of them along the roadside once we started through Towne Pass.

A few miles down the road on the other side we turned off onto the Emigrant Canyon Road to drive up to the Charcoal Kilns – and we got high enough for there to be snow on the ground.

A few miles down the road on the other side we turned off onto the Emigrant Canyon Road to drive up to the Charcoal Kilns – and we got high enough for there to be snow on the ground.

Because of their remote location these are some of the best examples of charcoal kilns in North America.

Because of their remote location these are some of the best examples of charcoal kilns in North America.

On the way back down from the kilns we branched off the Emigrant Canyon Road and took a six mile gravel road to Aguereberry Point. We came to a fork in the road and took the right one which led us to the site of the Eureka Mine.

On the way back down from the kilns we branched off the Emigrant Canyon Road and took a six mile gravel road to Aguereberry Point. We came to a fork in the road and took the right one which led us to the site of the Eureka Mine.

The left for took us up to Aguereberry Point we were treated to a fabulous view through Death Valley Canyon to Death Valley in the distance.

The left for took us up to Aguereberry Point we were treated to a fabulous view through Death Valley Canyon to Death Valley in the distance.

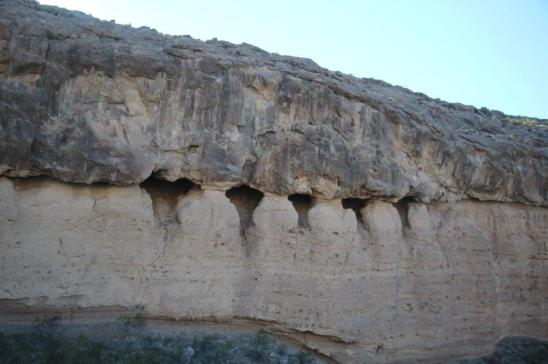

There was a nice turn-around parking area near the top but the road continued (very, very narrow) and wound (very, very tightly) around the highest point so we drove up to the top and then navigated the trail through the rocky cliff-face to check out the view, which was well worth all the dust and clambering!

There was a nice turn-around parking area near the top but the road continued (very, very narrow) and wound (very, very tightly) around the highest point so we drove up to the top and then navigated the trail through the rocky cliff-face to check out the view, which was well worth all the dust and clambering!

John looks like one of the rock out-croppings at the top of that rock.

John looks like one of the rock out-croppings at the top of that rock.

There is no guardrail on the cliff side and very few spots wide enough to pull over if you meet a vehicle coming up. You would need to do some tricky backing up. Thankfully that was not required.

There is no guardrail on the cliff side and very few spots wide enough to pull over if you meet a vehicle coming up. You would need to do some tricky backing up. Thankfully that was not required.

And once again, the sun is setting as we head to our hotel for the night.